Let People Move to Jobs |

October 21st, 2019 |

| housing |

Why are you trying to move more people into cities? There's lots of housing available in the US, it's just not in the currently trendy cities. Instead of moving people we should be moving jobs. Why couldn't Amazon have put their "second headquarters" in a deindustrializing city like Milwaukee instead of splitting it between DC and NYC?

The idea makes sense: these cities were built out for industries that have moved on, and now they're over-built for current demand. They have lots of buildings available, both commercial and residential, along with a lot of other underutilized infrastructure.

One way to look at it, then, is why aren't companies just moving there on their own? Company rent would fall, they could pay their employees less for the same standard of living or effectively give them all large raises by holding pay constant. Everyone would waste less time in traffic. The host city would be strongly supportive instead of somewhere between negative and neutral. What's keeping them put?

A major factor is that current employees don't want to move. If Google announced it was moving everything to Pittsburgh, ~80% of the company would quit. People put down roots and get attached to areas, generally more so than to jobs.

New companies, however, don't have employees they would need to move. Why do tech startups choose the Bay when almost anywhere else would be cheaper? I see two main answers: to be close to their investors and to be able to hire from a deep talent pool.

And this gets us to the real problem with "let's distribute jobs across the country": industries benefit enormously from centralization. Being in the main city for your industry means, for a start:

Good ideas flow more freely between organizations

Coordination between organizations is easier

Switching jobs is easier, so people don't get as stuck in jobs they don't like

Ease of switching also allows people to take larger career risks

People expected telecommuting to change this, but even though we have many technical tools that make remote work far more practical than it was even ten years ago, physically being in the same place as your coworkers remains extremely valuable.

Industries do vary, however, in how well centralization suits them. Three groups:

Industries that are distributed because they depend on resources that are distributed. People working in farming, logging, fishing, mining, and other industries spread out because the best places for those activities are spread out.

Industries that are centralized because they don't have location-based inputs. Software in the Bay, finance in NYC, film/TV in LA, biotech in Boston, commodities in Chicago, insurance in Hartford, etc.

Industries that need people. Doctors, teachers, barbers, auto mechanics, etc will all be a portion of your local population, and they'll mostly go where the people are. Centralization still helps, but people won't travel hundreds of miles to get their hair cut.

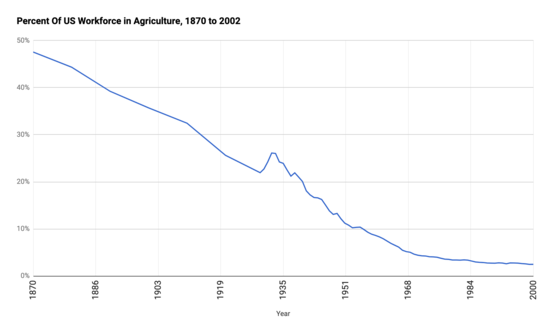

Many fewer people work in naturally-distributed industries than they used to. For example farming is down to only 2% of the population:

Thad

Woodman, Agricultural Employment Since 1870

An early example of a centralized industry was the auto industry, in Detroit. There was nothing about Detroit that made it uniquely good for producing cars, but as it became the consensus location for the industry it developed local culture and knowledge that had strong advantages for building cars.

Detroit also illustrates two major downsides of this centralization:

They stopped innovating so much. It was only because there were other major centers of automotive production elsewhere that we were able to get cars as reliable, safe, and efficient as we have today.

When their industry dried up, so did the city. Their cars weren't the best anymore, they lost business to Japan and others, massive layoffs, people moved away, the city is much worse than it was.

These two considerations mean we want:

A few key cities for each industry, so there can be competition at scales larger than individual companies. With international borders still being a major political force we'll probably be more towards the "less central than ideal" end of the spectrum for a long time.

Multiple industries in each city, so that as one industry in a city becomes more or less successful it isn't carrying the success of the whole city. If an industry does fail, others will be able to grow into their place. Reinventing Boston: 1630-2003 (Glaeser 2004) has a good description for how something like this has worked in Boston.

Overall, people working on the same thing in the same place as each other remains incredibly valuable, and we should let that happen. Instead of trying to distribute industries that are naturally centralized, we should let them centralize while managing the risks. Building more housing doesn't just let people move to where the jobs are, but also allows people working on other things afford to live in the city.

Comment via: facebook, lesswrong, hacker news