Index Fund Endgame |

November 5th, 2014 |

| money |

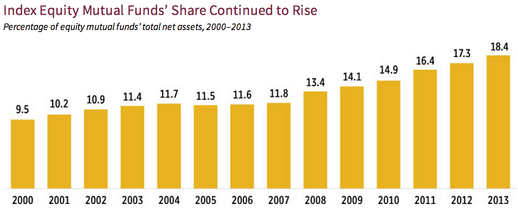

2014 Investment Company Fact Book

When A sells a stock to B the two are playing a zero-sum game. B believes the stock will go up, A believes it will go down, and they can't both be right. [1][2] There is a positive externality, however, in that the price they agree on becomes public and gives us all information about the stock. As people who notice their tendency to find themselves on the losing end of trades realize this and switch to index funds, the size of the actively traded market falls and the potential gains from better analysis fall. With less gains comes less effort, comes less useful prices. But does this matter to index investors?

Index investors want to buy a slice of everything. As the world becomes more prosperous the value of everything rises, so this makes money. The value of some individual things will fall, however, while others will rise, so you need some way to decide how much of each thing to buy. We could just buy a constant percent of everything, so 1% of Company Q, 1% of Company R, 1% of Company S, etc. But then if R and S merge, what do we do? Or what if someone founds a new company that does nothing profitable solely for the purpose of creating a stock that we'll want to buy 1% of? To fix this, we weight on price: if the total value of company Q is twice the total value of company R then we would like to own twice as much Q as R. If R and S merge this doesn't change our allocation, and if someone starts a new company its price will be very low so we won't buy much of it. So we're trying to buy a slice of everything in proportion to its value.

Which gives us a problem: index investors are dependent on the prices generated by active trading in order to decide how much of everything to buy and sell, but as index investing becomes more popular this price signal will get worse.

So what happens? Do enough people keep money under active management that the prices indexes use to decide how much of things to buy still work? Do index funds start to decrease in profitability as they take over more of the market because they're open to exploitation by active traders? Do companies start failing because stock price stops being useful to them?

[1] This isn't entirely right. Perhaps A works for Google and wants

to sell the company stock as it vests. Even though A is selling the

stock they may still expect it to rise in value over time, but because

they're a Google employee they stand to lose enough if Google starts

doing poorly that they would like to reduce their exposure to the

company. Ideally they invest the money from selling the stock into an

"everyone but Google" index fund, and now should expect similar

returns with less overall Google-correlated risk.

[2] Another possibility is that both of them agree the stock will go down if A holds it but go up if B holds it. For example, B could intend to purchase a large portion of the company, put in new management, and turn the company around.

Comment via: google plus, facebook